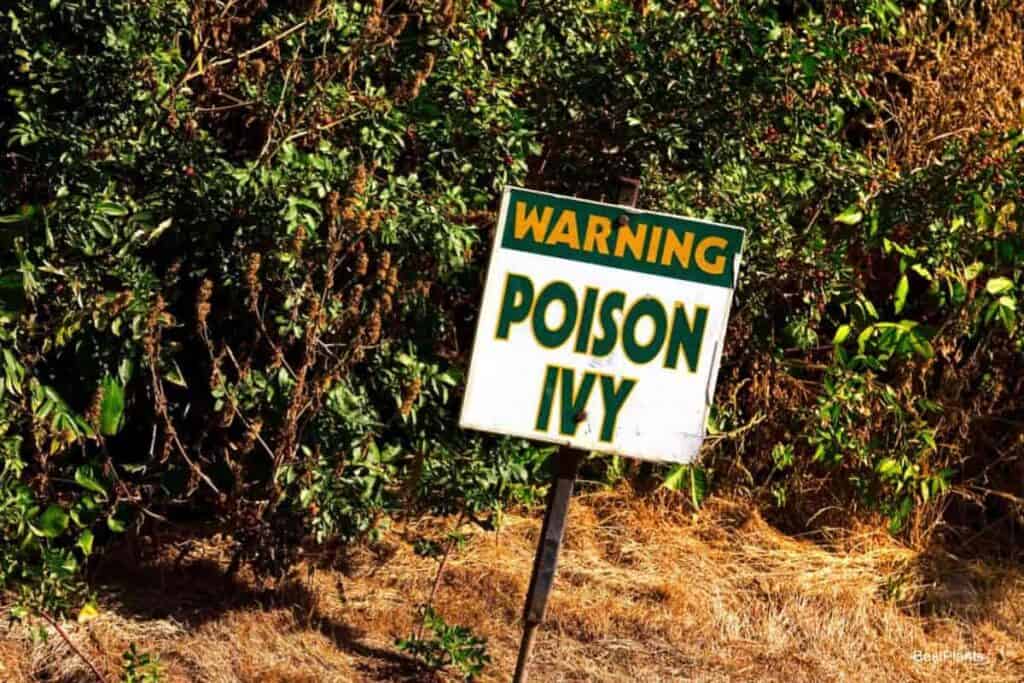

Every year, millions of people suffer itching, swelling, blisters, and even sometimes prostration and death by touching the poison ivy that grows anywhere from Maine to Florida and Nebraska.

The poison oak of the Pacific States has similar effects. Doctors and druggists are primed with cures, none of which seems entirely satisfactory to the patient—but perhaps they help.

Poison Ivy: Prevention

Prevention, in any case, works best.

Step 1 in prevention: Knowing poison ivy when you see it.

Step 2: Warding off skin irritation after contact.

In a moment, we’ll look at a new idea, simpler and easier than most of the old ones.

Know Poison Ivy’s Characteristics

First, let us look at the ivy itself and how its dire touch works.

The eastern plant, Toxicodendron radicans (Rhus Toxicodendron), grows as a vine, ground cover, or shrub.

Its long stems, clinging by aerial rootlets a fraction of an inch long, roam over fences and rocks or trail along under the dead leaves of the woodland floor, putting up everywhere the telltale three-parted leaves.

When well established, they stretch out stiff branches 4′ or 5′ feet long, against which your cheek or shoulder may easily brush.

Where poison ivy climbs a tree, it may develop a rope-like stem bristling with rootlets and often too big to put your hand around.

Don’t put your hand around it either, for the rootlets can poison you.

Often the birds sitting in harmless Boston ivy or English ivy that ornaments a brick wall may drop seeds of the poison ivy berries they have eaten.

These germinate at the base of the wall, mingle unnoticed with the innocent vines, and may poison anyone who passes too near.

Examine the ivies on your walls or your neighbors’. You may be surprised.

Unexpected Poison Ivy Invasion

Another unexpected invasion may come in the flower bed or the vegetable garden.

Do you know how to distinguish poison ivy seedlings among the weeds springing up?

The seedlings produce leaves with the typical three leaflets after they reach a height of 4″ or 5″ inches.

Before that, you could not easily spot them. Just handling those tiny seedlings may raise blisters on your hands.

Three leaves! A characteristic sheen! Small variations in the edges of the leaves!

There are the main keys to identifying poison ivy.

Unless you know just how the green of the leaves darkens through the season, get some friend who can identify the leaves to take you for “a poison ivy walk.”

Practice until you can spot the characteristic three-leaf cluster every time. Then, learn how to tell nonpoisonous three-leaf plants by their different color.

Different Species Resembling Poison Ivy

The poison oak of the Pacific coast, Toxicodendron diversilobum, resembles poison ivy but tends more to shrubby growth.

Worse is poison sumac or poison ash, Toxicodendron vernix, found anywhere east of the Mississippi, but only in bogs and wet places.

Its smooth, toothless leaflets look more like those of ash than sumac. The leaf stalk, however, is commonly red.

In fall, poison sumac’s white berries mark it plainly like those of poison ivy.

It takes its toll among blueberry pickers, as few others walk in the bogs. Occasionally though, it springs up on the bank of a resort lake or along a stream.

How Poison Ivy Works

Now, how do all these various vines and trees poison you?

Susceptible persons swear they have only to walk near poison ivy when the wind blows across it, and they will come down with the distressing symptoms.

This isn’t true at all. Most of us are unobservant, failing to notice what leaves we touch.

Peter Kelm, the amiable Finnish botanist who explored North America before the Revolution, said, “I was acquainted with a person who, merely by the noxious exhalations of it (poison sumac) was swelled to such a degree that he was as stiff as a log of wood, and could only lie turned about in sheets.” Well, maybe. Poisoning even from touch is rarely that bad, though bad enough.

Every part of the plant, living or recently dead, is more or less covered with minute droplets of a sticky oil—the poison.

These droplets are picked up by your skin when it touches the ivy. After several hours, the oil eats into the skin, and itching begins.

Depending on your reaction, you may blister or swell, or both, or you may feel no ill effects, for some persons are immune part or all of the time.

If, after being poisoned, you wash, as most of us do instinctively, the poison spreads, and the symptoms intensify.

Yet nearly everybody will now advise you to wash with yellow laundry soap.

Provided you wash before the itching starts, and further provided that you use a great deal of the strongest yellow soap, you will benefit.

Otherwise, washing seems to be disastrous. And at least one of my friends would rather have ivy poisoning than the effects of that soap.

Removing Ivy Poisoning

Think a moment.

On your skin are droplets of sticky oil too small to see. They must be removed immediately.

Is there no other way to get them off except to neutralize the oil with soap?

Yes, there is a way. You can blot them off.

Use anything dry. The first material I tried was dry peat moss. Perhaps you have a bag or bale of it in the garage, waiting to go on the flower beds.

Just rub a lot of it over the exposed skin anywhere you could have touched the ivy.

Or maybe you are away from home. Then, dry dust or fine dry sand will do nearly as well if you rub thoroughly.

But suppose you have merely brushed a poison ivy leaf with the back of your hand or your cheek. Then wipe it off with your shirt sleeve, and you will not be poisoned.

However, suppose you have accumulated a quantity of poison on your skin and wiped it repeatedly with the same sleeve. In that case, the sleeve may become sufficiently impregnated with poison to do some harm of its own.

You can get ivy poisoning from the hair of the dog, even though the dog is immune.

The worst cases of ivy poisoning often come from the smoke of a fire in which poison ivy is burning.

The oil droplets then float through the air on particles of carbon or carbon compounds that compose the smoke. So beware of the smoke from burning brush or leaves.

Killing Poison Ivy: Another Prevention Method

Eating poison ivy leaves may cause severe illness and, rarely, death.

An ancient claim was that immunity could be gained by this method. Do not believe this!

For immunity, it is much safer to consult your doctor, who can give you a serum prepared for the purpose.

There’s one other part of the prevention method. It comes after you learn to identify poison ivy in its various forms.

The vines and shrubs can be killed with 2,4-D sprayed heavily on a warm day or with Ammate, a DuPont chemical.

If poison ivy is mixed in with other plants, there’s a way to keep it from destroying them.

Wear heavy gloves, and put several leaves of each poison ivy plant into a milk bottle partly filled with a solution of the plant poison.

The plant will absorb the poison and die within a few days; neighboring plants will not be affected.

This is easier and more effective than pulling up all the poison ivy vines.

Cautions:

- Throw the gloves away after use.

- According to directions, mix plant poison, or the 2,4-D type that kills by hormone stimulation.

Summarizing, then—Don’t touch! Recognize the plants! Kill them! If you have touched, first blot dry, and wash as soon as possible.