Many people have delightedly exclaimed over a brilliant patch of the little red-crested lichen, or British soldiers, growing on sterile soil.

They have gathered it for dish gardens and table decorations or noted the widely-spreading, grayish-green tufts of the so-called reindeer “moss,” one of the commonest soil lichens.

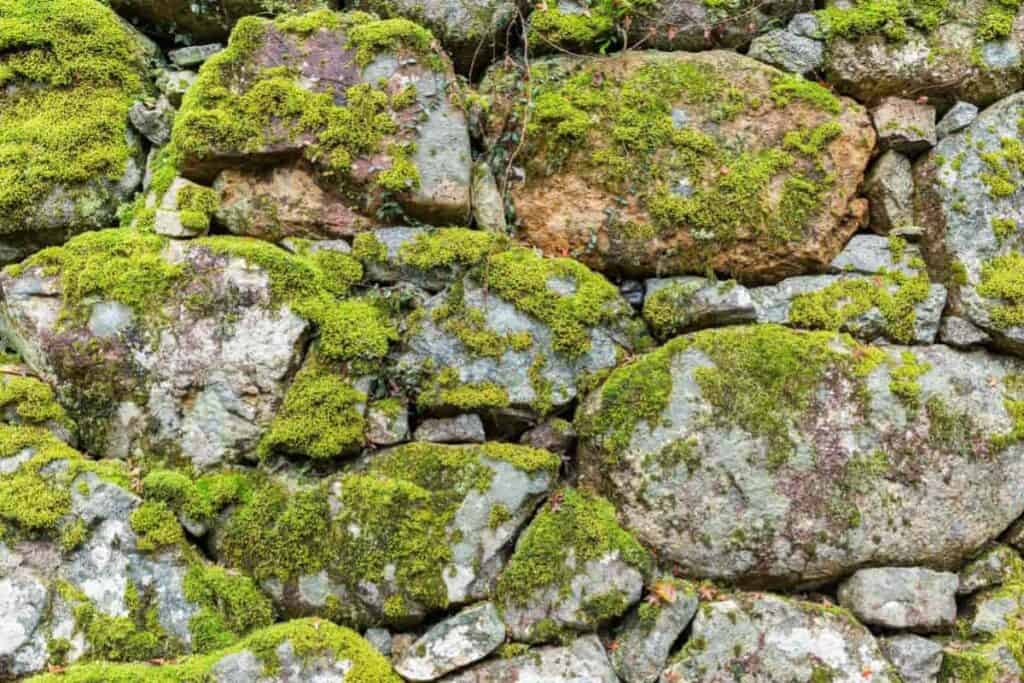

But the soil lichens are not generally as attractive or as prominent as the rock ones.

These rock rosettes, or “doilies,” adorn bare rocks and cliffs visible for great distances.

Many of these attractive species are within easy reach of one who walks afield, except in the region of cities, for lichens cannot grow where the air is tainted with smoke or the fumes of industry.

Noticeable Rock Lichens

The rock lichens are especially noticeable on humid, damp, or rainy days.

Just what is lichen? A lichen is a partnership between a fungus and an alga, a close association between a mass of fine fungal threads entangling a multitude of little green cells of an alga.

The algae most commonly present in this alga-fungus combination usually belong to the Bluegreen Group, Cyanophyceae, or the Green Group, Chlorophyceae.

The algae can live “wild” without the fungus, but in general, the fungus threads soon perish if they do not come across the appropriate algae.

Body Of Rick Lichens

The body of many of the rock lichens, generally of a rosette form, consists of a particularly tough and resistant sheet of tissue made up of closely-felted fungal threads that completely protect the delicate little algal cells enmeshed within.

The fungal threads afford shelter to the algal cells, and the algal cells manufacture food for the fungal threads, so “they live happily ever after.”

Adaptable Lichens

Of all the members of the plant world, the lichens possess the greatest capabilities of adapting themselves to the most widely divergent conditions of climate, altitude, moisture, drought, heat, and cold.

They spread from the tropics to the poles, increasing their numbers from the equator northwards and southwards.

These are the first growths on naked rocks and bare cliffs that offer neither foothold nor nourishment for other plants.

With their acids, the lichens can dissolve the rock-forming minerals, thus breaking up the rock and securing a firm footing.

They are, therefore, the pioneers who prepare the substrate upon which mosses and other minute growths can secure an anchorage and food.

They live partly upon mineral solutes and partly upon microscopic airborne particles but chiefly upon the products of the photosynthesis of their entrapped algal cells.

After a period of growth, rock decomposition, and decay, these hardy pioneers have thus prepared the surface of the rock for the succession of higher plants that follow, which further carry forward the transformation of the rock into soil.

Universally Distributed Lichens

Lichens are the most widely disseminated of the larger plant forms.

One species of interest in this respect is the green map lichen, Rhizocarpon geographicum, or Lecidea geographica, (shown in the drawing), said to be the most universally distributed larger organism of any kind.

It is found literally to the ends of the earth. It is the highest-growing of any of the plants of the Alps and was the only plant growth found by Agassiz near the summit of Mt. Blanc.

It has been collected at 10,000′ feet in the Himalayas, where it occupied the very last outpost of vegetation.

The same species has been reported from Mt. Chimborazo in the Andes.

This is the little lichen that so attractively colors and makes more cheerful the forbidding bare summits of our Adirondacks, Green Mountains, White Mountains, and others, splashing its little rosettes of bright apple-green thickly over the naked rocks.

But other species also lavishly decorate our northern mountains’ austere cliffs and ledges.

It was reserved for the Second Byrd Antarctic Expedition to discover the most southerly existence of plant life.

This was in the form of tiny lichens (not yet, I believe, determined as to genus or species) — lichens no bigger than the heads of pins growing on the northern exposure of a mountain.

Here for only a week or so in midsummer, the temperature rises above freezing. This short time is the only growing season for these minute atoms of life.

Attaining Great Age

As to our known rock lichens, it has long been supposed that some of them may attain a very great age, though the records are fragmentary and scattered on this subject.

One finds such statements as these, for example:

- “Some species growing on the primitive rocks of the highest mountain ranges of the world are estimated to have attained the age of at least 1000 years.” (Lindsay).

- “One crust lichen, Variolaria, has been known to increase one-half millimeter in size between the end of February and the end of September.” (Elliot).

- Some lichens “grow two or three years rapidly. Some have been known to be 45 years old before beginning to bear fruit.” (Creevey).

- “We have no data from which to ascribe the age of tartareous species which adhere almost inseparably to the stones. Some of them are probably as old as any living organisms on earth.” (MacMillan).

This authority also hazards the opinion that some rock lichens may date back to the retreat of the last glacier. In this country, this would mean something between 25,000 and 50,000 years.

Botanical Study of Parmelia Genus

Our longest and most careful study was made of three plants of the Parmelia genus, the commonest genus of rock rosettes on mountains.

The plants selected were three closely associated individuals of Parmelia centrifugal, a tightly adherent, thin, resistant species that grows at a higher altitude than most other members of the genus.

The botanical and mathematical details of this study were reported in the Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club in January 1948.

The gist of this study is that the average growth rate of all these plants together, measured over seven years, was only 0.85 millimeters a year.

This was at an altitude of 2,100’ feet, where growing seasons are much longer. Higher, above 3,200’ feet, on Mt. In Chocorua, New Hampshire, we found large rosettes whose age must have been 1,500 years or more.

Through binoculars on inaccessible cliffs some 10,000’ feet or more in altitude in the Alps, we have recorded far larger patches that we judged may have begun growing some 10,000 years ago.

So it seems reasonable to suppose that lichens represent the oldest living beings on our earth.

Age-long Chain Of Growth

Of course, this does not mean that the plant tissue we see now has existed over that period, for the central point of original growth in these great rosettes has disappeared, and only a ring of younger growth may persist.

The inner portion of the rosette is often occupied with subsequent concentric frilly lobes, or mosses, which have lodged upon the decomposing tissue of the original earlier zones of lichen.

But however that may be, these plants carry downward the succession of an age-long chain of constant growth.

The life of such lichens is maintained under the most trying of conditions.

On the very lofty mountains, growth must be exceedingly slow, half, quarter, or probably much less than a quarter of the rate we found by measuring the New Hampshire lichens already described.

Moreover, it is known that lichens can live for long periods, probably many years, in a static condition, with no growth.

Hence the notion advanced by some botanists, and now upheld by the present investigations, that some lichens may date back from their beginning of growth to the time of the retreat of the last glacier is not fantastic.

The life of the rock-clinging lichens of mountains consists of a very short growing period.

For part of the time, they are frozen solid and again are baked to a fierce hot state of desiccation by the sun blazing down upon the rocks through the rarified atmosphere.

The Temperature Of The Rock

We measured the temperature of the surface of the rocks next to several lichen patches we were studying in the mountains and found it to be more than 144° degrees Fahrenheit — a temperature almost unbearable to the hand.

The nearby lichens were baked into a hard, apparently absolutely moistureless condition.

They crumbled in hand into a dry powder!

And yet there must have been viable, soft, living protoplasm within the cells, for when clouds enveloped the mountain for a few hours and soaked all the rocks, out the lichens came, bright and soft and fresh.

44659 by Ethel H. Hausman