If you want roses the easy way, grow climbers. A few plants on fences, arbors, or trellises will turn the small garden into a colorful getaway. Large gardens produce a breathtaking effect, where great masses can be used.

For some reason, many gardeners seem to overlook the possibility of growing climbing roses.

Perhaps it is because the glamorous hybrid teas and floribundas receive more attention in the catalogs, or perhaps it is thought that the vigorous, rampant, once-blooming varieties were so prominent a few decades ago have no place in the smaller garden lots of today.

Climbing Roses Varieties

Climbing rose varieties have been improved in recent years, the same as other types. The growth is more refined, and hardy types are now to be had.

As a group, the climbing roses include those varieties that produce long canes that require support. Most structures, such as fences, trellises, walls, arbors, pergolas, or posts, are satisfactory. Types with very supple canes make excellent ground covers for banks.

From a landscape point of view, no other kind of plant will give the same effect. Compared with different roses, climbers excel in permanence, reliability, and ease of culture.

There are several different climbing roses, and each is adapted to unique garden uses. First, there are the ramblers. They were derived primarily by crossing varieties of Rosa multiflora, the Japanese Rose, or Rosa urichuraiana, the Memorial Rose, with bush varieties. Probably the best-known example is Dorothy Perkins, introduced in 1901.

The ramblers are rampant growers developing flexible canes 15’ to 20’ feet long in a season. They produce dense clusters of tiny flowers two inches or less in diameter. The best blooms usually come from wood made during the previous Summer, and they bloom but once during the season.

The ramblers are a neglected group, and it must be admitted that they are somewhat susceptible to mildew. But mildew is not difficult to control by spraying or dusting with sulfur or copper fungicides, and every garden should have at least a few of these beautiful roses.

Related: How Do I Grow Roses

The Large-Flowered Climbers

Early in the twentieth century, Dr. Walter Van Fleet of the U. S. Department of Agriculture, and other hybridizers, began making crosses between Rosa wichuraiana and Rosa setigera, bush varieties and a new type of climber was developed having flowers two or more inches across borne in loose clusters.

Since the flowers were much larger than the ramblers, the varieties were called large-flowered climbers. They were hardy and vigorous and produced large, sturdy canes. So stiff and heavy are the canes on some of these varieties that they need little or no support and can be grown as shrubs if desired.

With the development of the large-flowered climbers, it became popular to grow them on posts or pillars, and the term pillar rose came into use. Pillar roses are not a distinct type, but rather the term signifies a method of support. Growing climbers on posts or pillars is still an excellent method, especially where space is limited and fences or similar structures are unavailable.

However, not all varieties are adapted to being supported in this way. Some fail to bloom well when trained upright, and some make such rampant growth that it is challenging to keep them attached to the post.

Climbing Roses Are Slow Bloomers

One of the severe drawbacks to the climbers is the lack of continuous bloom. Everyone wants climbers that will flower throughout the Summer like the hybrid teas, and the plant breeders have tried to develop them.

Progress has been slow, but a few hardy climbers give more or less bloom throughout the season. They are called everblooming climbers, but the word everblooming must be interpreted with reservations. Repeat or recurrent bloom more accurately describes the flowering habit.

For the warmer sections of the country, the climbing hybrid teas and climbing floribundas are exceedingly valuable, and they could likely be grown with considerable success in the colder regions if one will go to the trouble of giving them special protection.

Unless the plants are grown in a very protected spot, it is necessary to remove the canes from their supports and lay them on the ground. This, of course, maybe necessary even with the hardy climbers in icy regions.

The climbing hybrid teas and floribundas originated for the most part as climbing sports of the bush varieties. The flower color and form remain the same as the bush variety, but the habit is that of a climber.

While no type of rose is challenging to grow, climbers are perhaps the easiest. Once a plant is established, it will thrive indefinitely with little attention to soil preparation or fertilization. They are more tolerant of drought than most bush roses.

They are less injured by disease and insect pests and will get along with less spraying or dusting. It often takes a climber three or more years to become well-established, so one should not expect too quick results.

Pruning Climbing Roses

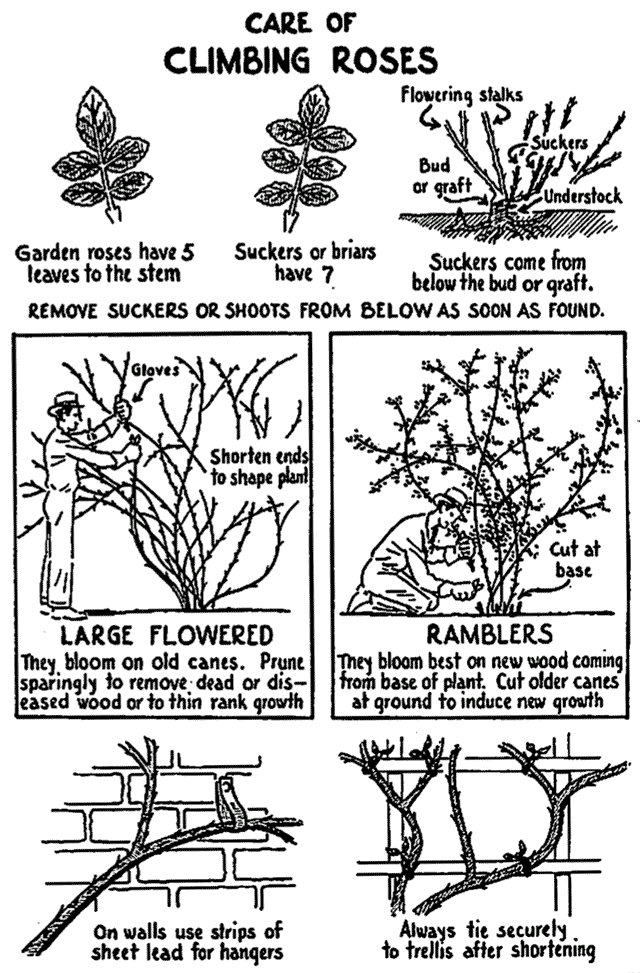

Pruning climbing roses is probably the most exacting part of their culture, especially in the small garden, because if they are left unpruned, they soon become a tangled thicket of briars that is an eyesore except when the plants are in full bloom.

Ramblers should be pruned as soon as they have finished blooming by cutting out all the canes that have flowered back to the ground level. Save the new canes coming up from the base and keep them tied to the support attractively.

Large-flowered climbers do not produce as many new canes as the ramblers, so removing all the canes that have flowered isn’t always practical. As new canes develop, old ones may be removed. After the petals wither and fade, remove the flower cluster leaving four to 12” inches of the lateral branch to produce flowers next year.

Only the flower clusters should be removed back to the first leaf below the group in the vice of the everblooming climbers. Some of the older ones can be removed when the canes become crowded. All climbers must be kept tied to their supports.

It is just as much fun to experiment with different varieties of climbers as it is with bush roses.

Read the description of the types in the catalogs you receive this Spring and try some that you have not grown before—experiment by increasing them in different ways and different spots in your garden. Use them lavishly, and you’ll find that they will give unlimited pleasure with a minimum of effort.