Few perennials are easy to grow and propagate or more varied in their colors and heights than the many kinds of hardy asters. Available in a wide color range, from white to many tints and shades of pink, rose, red, purple, violet, blue, and lavender, they range from six inches to six feet.

In diameter, the blossoms vary from a dime and smaller to the size of a silver dollar and larger. Likewise, there are differences in abundance, brilliance, and bloom time. Some varieties are more vigorous and easy to increase, while others are short and sturdy, requiring no support.

Thus, choosing types for almost any garden situation favorable to their growth is possible. Although hardy asters thrive best in moist, medium-fertile soils with plenty of sunshine, they can be grown successfully in any good garden soil.

Sources of Varieties

Asters are members of the composite family, including chrysanthemums, dahlias, erigerons, heleniums, and others. Although there are hundreds of wild species of asters, most garden varieties have been developed during the past 50 years.

By crossing compatible species, plant breeders, principally in England and America, have sought to combine the best qualities of each parent. The best garden varieties were developed mainly from the New York aster (Aster novibelgi), New England aster (Aster novaeangliae), Italian aster (Aster amellus), and a few other species.

Scores of varieties listed by horticulturists some 25 years ago, at the time I decided to raise hardy asters as a hobby, have now been replaced by newer and better kinds. Of over 100 in my collection, only a few are available today.

Too often, however, plants or inferior seedlings of such varieties, planted long ago, maybe seen in neglected gardens holding onto life and bringing no credit to the race.

Since the first garden varieties bloomed mainly in the early fall, at the time of the feast of St. Michael, the name “Michaelmas daisies” was given to toasters in England. On the other hand, some kinds bloom in the spring and the summer, with the result that American plantsmen have called them simply what they are—hardy asters.

Unlike the so-called China asters (Callistephus Chinensis), which are annuals, hardy asters are true herbaceous perennials, renewing themselves yearly. Plants may be increased extensively by divisions or cuttings.

A few years of experience with hardy asters convinced me that shorter, sturdier, and longer blooming varieties were needed. The flower colors of my plants were brilliant, but few remained in flower for more than two or three weeks.

Few also would stand up without staking. Therefore, I found that further breeding was needed and started on the search for wild asters with desirable characteristics.

Finally, a promising plant was found growing in beach sand below the high storm-water line on Oregon’s Pacific seashore. It was later identified as an aberrant form of Aster douglasi. The new varieties known as the “Oregon-Pacific” asters have been developed from it and its progeny.

Wonder of Staffa

The best-of-the-first of these cushion-type asters was a variety called Pacific Amaranth, so named because of its amaranth-purple flowers. The dwarf to semi-dwarf plants, with a long bloom season, are hardy and vigorous almost to a fault. Like that splendid perennial from Switzerland, Wonder of Staffa, a variety of Aster frikarti, the flowers are sterile.

This is a valuable characteristic since plants do not scatter seeds to clutter the beds with inferior seedlings in the manner of fertile varieties if not cut down after flowering. Sterility may also favor a more prolific bloom over a more significant period.

Aster breeding objectives have broadened through the years until the list of desirable traits is difficult to attain in any one variety. Distinctive attributes are large flowers in a wide color range, short, sturdy plants that will support themselves and bloom over a long period, and plants with maximum vigor to withstand severe climates.

A few years after Pacific Amaranth was released, variety Twinkle appeared. Dwarf and less aggressive, Twinkle is sterile and equally long-blooming and floriferous. With their unusual frosty-white centers, the amaranth-rose flowers suggested the named Twinkle.

More recent introductions include Persian Rose, a semi-dwarf with sterile flowers; Violet Carpet, a violet-blue with the prostrate habit; Canterbury Carpet, small canterbury-blue flowers; Snowball, released in 1956, a pure white dwarf, eight to 12″ inches high.

Planned for introduction this year are two new dwarfs. Bonnie Blue, 6″ to 10″ inches, and Romany, 10″ to 15″ inches, both medium-early with a long-blooming season. The medium-sized flowers of Bonny Blue arc a medium blue color, while Romany’s white blooms are roman-purple, about the size of a silver dollar.

However, they are not as large as those of Serenade, which is a semi-dwarf, introduced in 1955, with light lavender-blue blossoms up to 2″ inches across.

English Varieties

Serenade, derived by crossing one of my dwarfs with one of the new, large-flowered English varieties, is highly floriferous when in full bloom. Additional large-flowered, semi-dwarf selections have been obtained in other colors (on trial) using pollen from such English varieties as Plenty, The Dean, Ernest Ballard, Eventide, and Janet McMullen.

These are good ornamentals, with extra-large blooms, but too tall to stand without support. Another popular new English aster, not so tall, is Winston S. Churchill, which bears medium-size deep red flowers.

Though there is still considerable opportunity to improve hardy asters, horticulturists should be grown more often in our gardens. For example, dwarf varieties are excellent for use as edging plants or rock garden specimens.

Then, too, striking color effects can be produced with beds of hardy asters alone by selecting for range in height and other characteristics. They are splendid additions to the mixed perennial border or specimen plants in any spot needing late summer and autumn bloom.

Hardy asters make good-cut flowers, especially varieties like Mt. Everest and Violetta, with long, willowy branches. Solid aster (Aster solidago in-tens), with its tiny, creamy-yellow flowers, and the species heath aster (Aster ericoides), with its small, white blooms, give an airy effect in arrangements. The wonder of Sulfa is also excellent for cutting, as arc many other kinds.

In our garden, we enjoy growing color-designed chrysanthemum beds, using kinds of suitable heights and similar blooming habits. Satisfactory varieties of semi-dwarf, medium-high, and taller chrysanthemums are more accessible to obtain than suitable dwarfs for edging and extra-tali ones for background use.

However, these problems have been solved by using dwarf hardy asters for edging the chrysanthemum beds, with tall asters for extra height and accent in the background.

Sure of the tall New England asters, like Roycroft Purple, Incomparabilis, and Harrington’s Pink, are suitable varieties behind chrysanthemums. In contrast, such dwarf asters as Bonny Blue and Romany serve well for border edging.

We like Bonny Blue planted around an open bed of dwarf chrysanthemums and Romany, purple and slightly larger, to face a deeper bed to be viewed from the front. Some shorter novae-angliae asters would be helpful.

Hardy Asters Enjoy Good Culture Where Others Fail

Perennial hardy asters respond generously to good culture and can be used where other flowers fail. Despite their rugged nature, a good gardener will give them a fair chance by providing a good soil, plenty of moisture and sunshine, and some fertilizer. They will tolerate some shade, though they perform less well.

Plant dwarf aster from 12″ to 18″ inches apart, giving taller kinds more space. Those too tall to stand alone require early staking before they begin to sprawl, or they may be cut back to make them grow shorter and bushier. However, this is best learned by experience as it does not work equally well with all.

On the whole, asters are troubled by few pests. Yet, mildew may be a problem if plants are too thick or too shaded. Blister beetles, which sometimes move in to feed on the petals, can be controlled with an insecticide or handpicking.

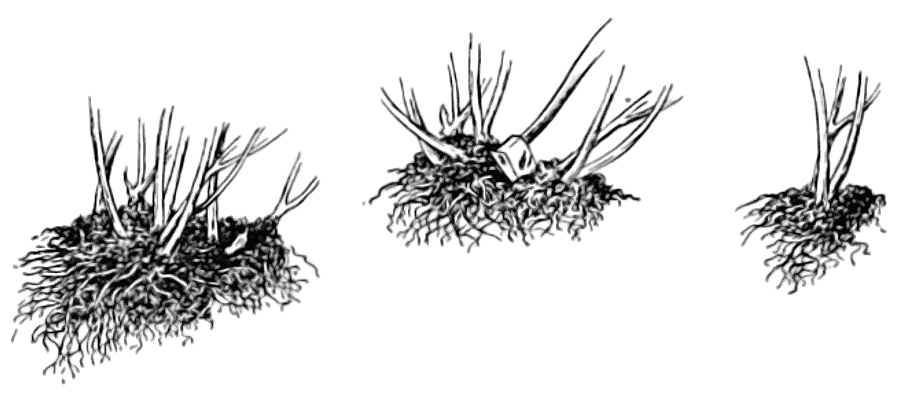

#2 – Tough crown may be separated with axe

#3 – Use outer stems for new plants

For success, an essential cultural practice is not to allow the clumps to become too large. Whenever they become saucer-sized or more enormous, divide them into chunks with four or five stems. Some plants require division every year, while others need it once in two to four years.

When dividing, which is a spring practice, keep the fresh young shoots from the outside of the clumps, using three to five for each new plant. Sometimes a single node will make a better flowering plant by fall than an overgrown old clump. Frequent division and good care pay dividends in thrifty plants with profuse and brilliant bloom from midsummer through autumn.

44659 by Leroy Breithaupt